Lecturas

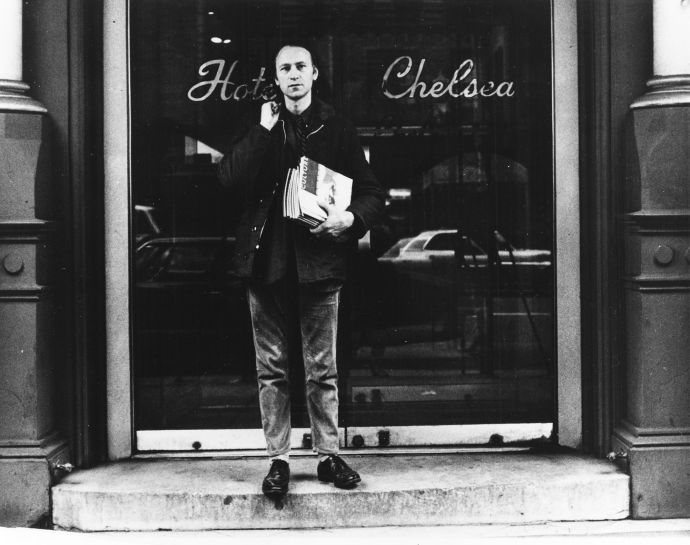

Jonas Mekas was the co-founder, in 1954, of the seminal publication Film Culture. He was the first film critic of The Village Voice, and his self-chosen beat was the noncommercial cinema. Mekas founded the Film-Makers’ Cooperative and then, in 1970, Anthology Film Archives. He’s also a filmmaker. Any of these activities would establish him in the history books as one of the most important modern movie-people. But the activity that’s suddenly in the forefront is his critical writing: his “Movie Journal: The Rise of a New American Cinema, 1959-1971” has just been reissued by Columbia University Press, and it’s a cause for celebration—and consideration. The original edition, from 1972, is long out of print. The book is a rich trove of cinematic wisdom, an artistic time capsule of New York at a moment of crucial energy, and a reflection of controversies and struggles regarding independent filmmaking that endure to this day.

📚Jonas Mekas, Champion of the “Poetic” Cinema. The New Yorker.

En écho à la rétrospective « Manifeste. Le Cinéma Corporel », consacrée à l’œuvre de Maria Klonaris et Katerina Thomadaki au Jeu de Paume, le magazine réédite ici trois de leurs nombreux Manifestes, une forme littéraire privilégiée qui, sans être exclusive, correspond en effet à leurs engagements et a toujours accompagné leur pratique artistique. Nous avons choisi leurs trois premiers manifestes, publiés à Paris entre 1977 et 1979, ainsi que leur préface à l’édition d’un recueil de ces textes aujourd’hui épuisé.

📚Klonaris/Thomadaki Manifeste.

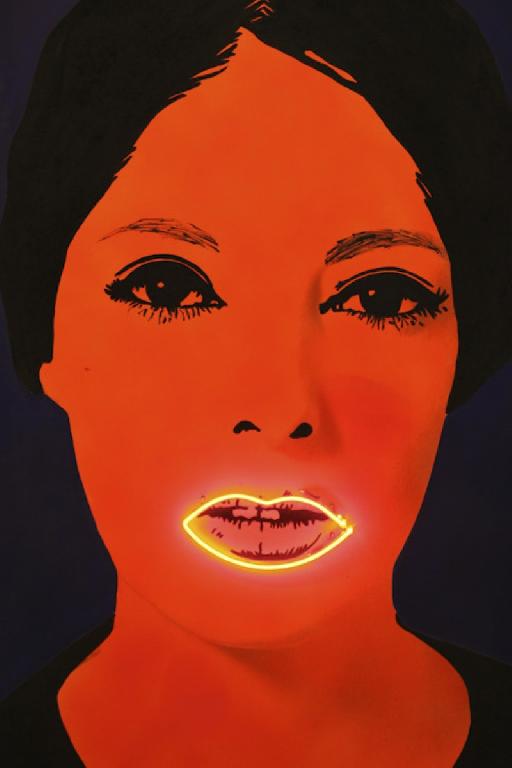

A cornerstone of Sturtevant’s work was appropriation — before appropriation became a thing. She produced her own versions of Andy Warhol’s Flowers paintings and Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit at the start of her career. For more than a decade, Sturtevant stopped producing work after continuous negative critical reception.

📚Underappreciated Women Art Pioneers of the ’60s. Flavorwire.

An unfinished film can be any number of things: the sketchy shambles of a work to be reconstructed in the imaginations of its audience; a partial, suggestive film, beleaguered by jagged seams and brusque transitions; an overabundance of material, never edited; or a work that’s pre-programmed for incompletion, dictated by an artist’s antipathy for finitude or determination. In The Unfinished Film, the cinema sidebar to the Met Breuer’s marquee opening exhibition, Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, programmer Thomas Beard pursues “a secret cannon” of such films, seeking out the fragment-ridden underside to the official cannon of finished, more thoroughly acculturated works.

📚The Ambiguity of Films Left Unfinished. Hiperallergic.

Watching a BBC television programme on the history of the UK and the European Union the other night (Europe: Them or Us), I noted the great amount of archive footage used and how skilfully it had been woven into the argument. I looked, as I always do on such occasions, at the credits, to see from where the footage had been taken, and who had been the researcher. Happily all of the archive sources were named and the likewise the researcher, Alex Cowan. Now I can remember him when he was just starting out in the business, probably in the late 1980s, and it got me to thinking about the overlooked art of the footage researcher, and how much they as a profession have contributed to history and culture.

📚Films beget films.Luke McKernan.

Zanny Mellor’s paintings and photograms explore states of flux and impermanence through the application, manipulation and erasure of paint.

Here, she gives an in-depth interview about her painterly practice.

📚Zanny Mellor.Traction Magazine.

I’m growing more and more anxious. Even though I am more self-assured now, my need to always do better and improve myself is stronger. I must seem very worried and concerned most of the time – and it’s because I am. My work carries great responsibility.

📚Ennio Morricone. The Guardian.

Called Fritz Lang’s first great movie, even by him, Destiny (1921) displays a fluency of visual expression that marks silent-era masterpieces to come as well as the primitive devices cinema is about to leave behind. Episodic in structure, Destiny is a woman’s quest to retrieve her beloved back from Death, a quest that takes her from a German small village “that time forgot” even further back in time, first to the City of Believers during Ramadan in some fictional Baghdad, then to Renaissance Venice during Carnival, and finally the imperial court in ancient China, in what are basically chases through a series of elaborately rendered set pieces. While each epoch is distinct, they are linked by a thematic architecture: archways, pillars, walls and stairs reduced to simple iconic forms in a fusion of Gothic, Eastern and Modern influences, forging an optimistic harmony among geographies, time periods, peoples and even beliefs. Despite its retrograde notions of the exotic, the film is full of fancy and wonder, danger and excitement—a fairy tale, albeit of the Grimm variety, come to life for grownups.

📚DESTINY Calls.FANDOR.

Dans ce dialogue avec Harun Farocki, publié dans la revue Filmkritik, en février 1980 et Juin 1981, Peter Weiss revient sur son rapport au cinéma et sur son passage du film à l’écriture. Les deux hommes s’interrogent sur ce qui fait la spécificité de l’expérience et de la représentation filmiques, en explorant les films majeurs de Weiss tout en les replaçant dans la globalité de son œuvre. Ce texte est précédé d’une introduction de Thomas Voltzenlogel.

📚Le film comme étude : dialogue entre Peter Weiss et Harun Farocki. Période.

A British artist who works and resides in Berlin, Tacita Dean has for the last eighteen months been living in Los Angeles. Drawing on the daily experience of this changed milieu—indicated by the title of the current exhibition—Dean was inspired by what she hadn’t expected, which caused her to jettison preconceived ideas of work she might do in California.